Part 2: Do We Need to Meet? The Environmental Impact of High Meat Consumption

Hi, in the previous part, we discussed the trend of increasing meat consumption, its impact on human health, and various aspects of vegetarian diets. In this article, I propose to focus on how excessive meat consumption affects the environment and the ecology of our planet as a whole, as well as certain aesthetic aspects.

Animal husbandry is a significant source of carbon dioxide emissions, including methane (CH4), nitrous oxide (N2O), and carbon dioxide (CO2). According to the FAO (Food and Agriculture Organization) [11], this sector of agriculture accounts for 8-14% of global emissions. It is worth noting that there are substantial discrepancies in the estimates across different sources. However, the undeniable fact is that the negative impact of animal husbandry on the atmosphere is palpable.

Growing feed crops for livestock requires significant resources, including fertilizers, which cause nitrous oxide (N2O) emissions—a potent greenhouse gas. Emissions of N2O from agriculture account for approximately 2.5-3% of the total amount of all negative emissions.

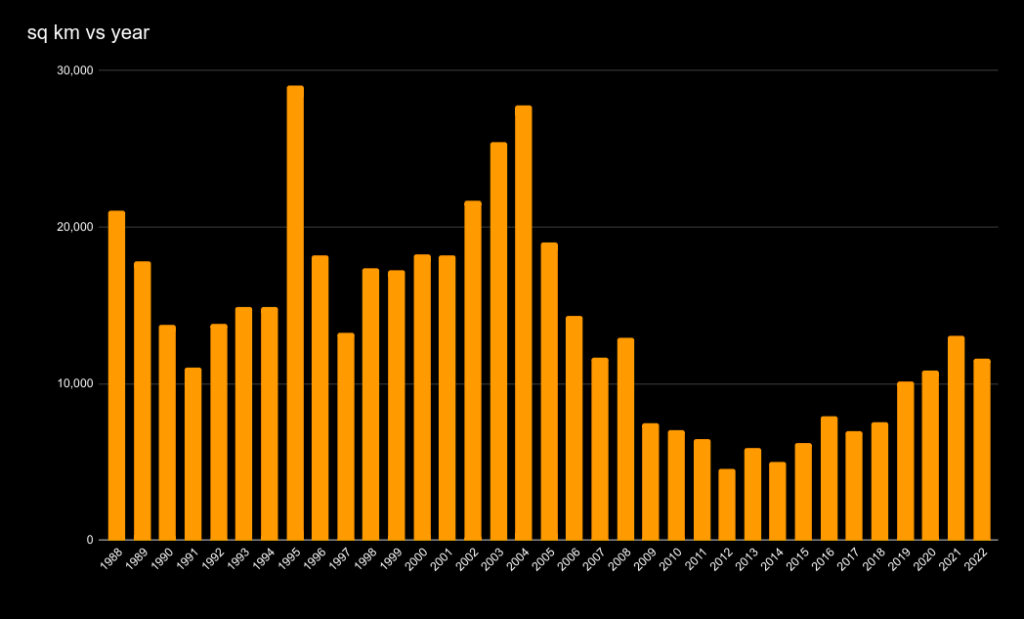

This also leads to deforestation and land-use changes, which in turn cause significant CO2 emissions due to the loss of forested areas that are important carbon sinks. The worst situation is observed in Brazil. According to the INPE, From 2000 to 2018, about 17% of the Amazon rainforest was destroyed to meet the needs of livestock—specifically for growing feed crops and creating pastures for cattle. To express these percentages in square kilometers, it can be confidently stated that the area of deforested land in Brazil is at least equal to the area of all of Germany.

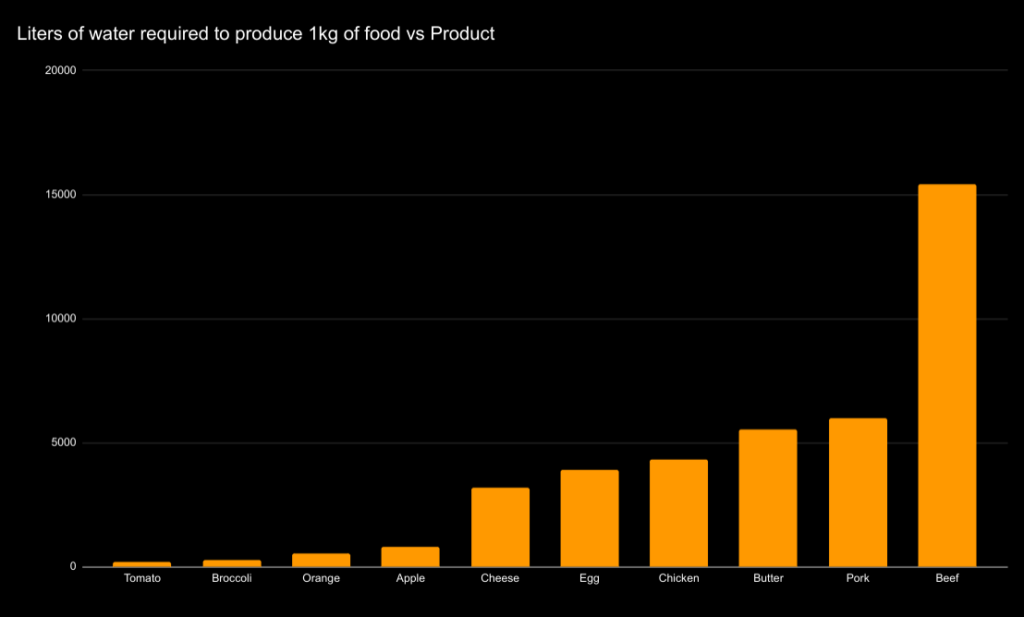

Meat production requires about 27 km³ of water annually, which is equivalent to nearly 18% of the volume of Lake Tahoe, which contains approximately 150 km³. In comparison, the total annual water consumption for drinking needs for all people on the planet is approximately 0.024-0.039 km³, indicating the enormous resources needed for animal husbandry compared to personal needs.

However, these numbers are not as alarming as the amount of water used specifically for meat production in the industrial sector, as well as how much water is used for irrigating fields for animal feed. In the case of irrigation, the situation looks even more dramatic when considering the pollution of water by pesticides and other harmful chemicals (this aspect goes beyond a single article).

Recent estimates suggest that producing 1 kg of beef requires, attention, 15,000 liters of water, while 1 kg of pork requires 5,000 liters. The next time you eat a burger at McDonald’s, consider whether it is truly as cheap as it seems. Frankly, when evaluating industrial meat production in terms of resource efficiency, it turns out to be an extremely costly and resource-intensive process.

If that were not enough, there is also an extremely negative ethical aspect of rapid and mass meat production—namely, the conditions in which animals are kept. And while in many countries, standards have significantly improved, we all know that the overall situation remains unsatisfactory.

So, if everything is so bad, should we give up meat altogether? Unfortunately, even if we momentarily forget about the high protein and protein needs for children and the element of high adaptability in extreme conditions (discussed in the first part), it turns out that the absolute exclusion of meat consumption from the diet and its complete replacement with plant-based products is practically impossible. Moreover, such an approach is not significantly better for our planet than the current environmental situation <-> animal husbandry. If we follow this concept, the word “animal husbandry” would simply be replaced with “plant husbandry,” and instead of one set of negative consequences, other consequences would arise.

For instance, the amount of plant biomass consumed by humans would increase exponentially. Disposing of such a large quantity of biowaste in landfills is incredibly irrational and ineffective. As of today, most of the bio-residuals from plant-based food production for humans are consumed by animals. A significant amount of plant residues could create substantial disposal problems. Far from all pastures can be transformed into fields for cultivation, and a significant increase in the area allocated for vegetation would also lead to increased water pollution.

It should also be noted that in many hot regions, animal products and meat are practically the only viable dietary options. Personally, I believe that an absolute rejection of meat is not only a “vegetarian utopia,” but also an ineffective solution. In everything, moderation is necessary, and the truth always lies in the “golden mean.” The energy circulation: plants → animals → humans is not a scientific fabrication, but is created as a result of millions of years of evolution. None of the extreme solutions are optimal.

Daily consumption of burgers and hot dogs is a direct path to diseases and premature death. The lack of sufficient proteins during the body’s development (especially in terms of skeletal and brain growth) through ill-considered vegetarian/vegan diets, in my opinion, is a dire extreme.

What if we try to find some balance of state? The commonly accepted norm of moderate meat consumption for an adult, so that it does not harm health, is around 15-30 kg per year (depending on various sources). For instance, let’s consider a family with two or three children and two adults. For proper and safe development, considering that a child consumes almost half as much meat, a total of 30 kg of meat per year would be quite sufficient. Adults would need 15 kg per person—this would positively affect health, and as they age, this quantity could even be reduced. Therefore, for such a family, a total of 60-70 kg of meat per year would be entirely adequate.

Thus, the global production of meat (with moderate and rational consumption) could easily be reduced fivefold—without significant difficulties from extreme approaches. Animals would have better living conditions, meat could be more expensive but of higher quality, and the environment would function in balance rather than on the brink of its capabilities.

I can’t help but recall my childhood. My grandparents kept a pig that grew on food scraps from the table and plant leftovers. There were no pesticides, and the living conditions were more than acceptable (a pen in the summer, warm bread in the winter). Yes, the pig lived only for a year, but half of its carcass provided for the entire family, while the other half was sold. I don’t remember ever feeling like I lacked meat or wanting it more or more often. I can confidently say that meat was not on the table daily, and that was absolutely unnecessary. The diet was balanced—vegetables, fruits, fish, honey, nuts—all grown in our garden. The quality and taste of the products I remember from my childhood are practically impossible to find today in large cities.

Modern norms of meat consumption are a clear mistake that has an extremely negative impact on health and the environment. An absolute rejection of meat for all of humanity is also not a solution. Personally, after all my research, I remain firm in the following position: moderate and necessary consumption of meat for children is essential, as well as a gradual reduction of meat consumption for adults from 30 kg to 5-10 kg per year, with the possibility of transitioning to a vegetarian diet supplemented appropriately.

To not miss out on fresh articles, useful tips, and exclusive materials, I suggest subscribing to the newsletter:

Thank you for your attention, Lumin Hopper

Please note: this article is for informational purposes only and does not constitute medical advice. Before making any decisions regarding your health or diet, we recommend consulting a qualified professional.